Antahkarana Shuddhi for Moksha – Part II

The purification of the antaḥkaraṇa is a prerequisite for self-knowledge. What are the obstacles to self-knowledge? What are the means by which one prepares the intellect for self-knowledge? To explore these questions, this blog examines the components of the antaḥkaraṇa and the means by which it is purified in preparation for mokṣa.

This is a two part blog. The first part was published here – Adhikara Sadhaka.

The Significance of Antaḥkaraṇa Śuddhi in the Pursuit of Mokṣa.

For a mumukṣu or seeker of Brahman, stabilizing the material body is necessary for success on the path to realization. Without a healthy body, neither the focus nor commitment required to pursue this parā vidya or the highest knowledge is possible. In fact, the Upanishads advocate the physical strength and health of the sharīra as prerequisites for study. But, once the physical body is stabilized, the subtle body must also be made steady. Higher elevation, purpose, and awareness come only through the advancement of the subtle body.

A significant component of the subtle body is the antaḥkaraṇa. Commonly simplified to mean “the mind,” antaḥkaraṇa comes from the Sanskrit compound: “antar,” meaning interior or within, and “karaṇa,” meaning sense organ or cause. Therefore, antaḥkaraṇa is the inner cause or internal organ that controls the entire psychological process, including emotions.

The antaḥkaraṇa is constituted of four psychological faculties:

- Manas – the mind

- Buddhi – the intellect

- Ahaṃkāra – the ego

- Citta – memory

“Shuddhi” translates from Sanskrit to mean purification or freedom from defilement. Therefore, antaḥkaraṇa śuddhi means cleansing the inner organ (by removing unregulated sense desires) and preventing further desecration.

How has the Antaḥkaraṇa become impure?

Yama explains:

“अन्यच्छ्रेयोऽन्यदुतैव प्रेय- स्ते उभे नानार्थे पुरुषँ सिनीतः ।

तयोः श्रेय आददानस्य साधु भवति हीयतेऽर्थाद्य उ प्रेयो वृणीते ॥

anyacchreyo anyad utaiva preyaste ubhe nānārthe puruṣam sinītah tayọh śreya ādadānasya sādhu bhavati, hīyate rthad ya u preyovṛnīte

Different is the good, and different indeed is pleasant. These two, with different purposes, bind a man. Of these two, it is well for him who takes hold of the good, but he who chooses the pleasant fails of his aim.”

~ Kathopanishad 1.2.1

The physical body, directed by the subtle body, chases the world of sensual pleasures (the pleasant.) Jīvas, who, through avidya, identify as the śarīra (body,) have become bound by the pursuit of fleeting perceptions of pleasure[1] associated with the śarira and the jagat. But the enjoyment of the phenomenal is transient, and due to the law of diminishing returns, consumption results in decreased satisfaction. And so, the more we consume, the less “happiness” it brings, resulting in more abundant and intense stimulation being sought. This sullies the antahkaraṇa and further entangles the jīva in a web of sense desires. Consequently, the jīva does not find an apparent escape from saṃsāra to mokṣa.

How does one attain Antaḥkaraṇa Śuddhi?

Descartes said, “I think therefore I am.” However, vedānta advocates that existence precedes thought. By understanding the four functions of the antaḥkaraṇa, the seeker becomes more conscious of what is happening within his internal organ and what drives his behaviors.

How the Antaḥkaraṇa works

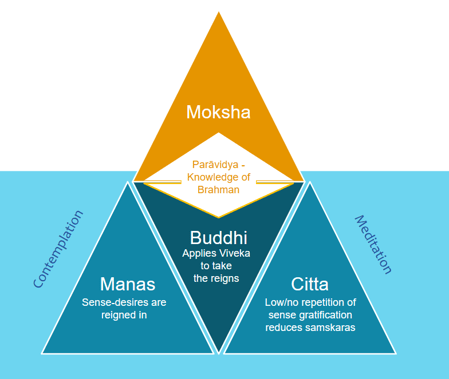

Figure 1: How the antahkaraṇa works

- The Manas: The mind is the seat of desire which controls will or resolution (saṃkalpa). It interacts with the senses and receives external stimuli. Due to saṃskāras developed and strengthened over many lifetimes, the manas decides whether an experience is desirable (rāga) or displeasing (dveṣa.) The manas sends the information about the experiences to the buddhi for processing.

- The Buddhi: The buddhi is the intellect that uses the power of discrimination (viveka) to express rational control over decision-making. A reciprocal relationship exists between viveka and parā-vidya. The ability to differentiate between the real and unreal, permanent, and temporary, self and other-than-self comes from knowledge. Conversely, the greater the knowledge, the stronger the power of viveka.

- The Ahaṃkāra: “Aham” means I, and “kāra” means to do with. The ahaṃkāra, which results from avidya, causes the Ātma (Self) to identify with the body as “I”—the doer. It builds a unique sense of identity, separating Ātma from Paramātma. Once the ahamkāra takes on an independent individuality (ego) and sense of “I-ness,” the buddhi is subjected to that identity and functions only in that context.

- The Citta: The citta is the higher mind or consciousness that acts as the storehouse of the jīva’s karmas and samskāras over lifetimes and carries their imprints from birth to birth. This build-up of impressions on the mind prevents the self from perceiving anything in its true state—even its own self. To overcome this ignorance, it is necessary to cleanse the citta.

The buddhi receives the information from the manas and analyzes it using reasoning, allowing a choice to be made rather than simply responding to the experience. The manas and buddhi's continuous activity is choosing between the right, the good, and the pleasant[2]. When the buddhi becomes silent, there is no viveka or discrimination.

The sensual desire-driven manas and ahamkāra work together to circumvent the buddhi and guide our actions towards sense-enjoyment that strengthen saṃskāras and reinforce a separate sense of identity.

Reshaping the Antaḥkaraṇa Shuddhi = Untying Knots

We are told that the antaḥkaraṇa resides within the heart. The Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad speaks about the knots we tie within the heart.

We're all often in the process of tying knots[3] through saṃskāras. When the sense organs encounter sense objects, an experience is created, and there is a reaction in the manas. This includes likes, dislikes, frustration, sorrow, anger, fear, insecurity, loneliness, etc. The response toward our experiences defines the knots of our hearts, including the rāga-dveṣas, sukha (happiness), and duḥkha (sorrow). Knots become tighter by repeating the experiences and our reactions. The continuous pursuit of rāgas and avoidance of dveṣas keeps the manas preoccupied with the senses, unable to fix its aspirations for higher goals.

The knots of our saṃskāras must be acknowledged and observed before we can deal with them. This happens through meditation and contemplation, removing the mind from the chaos of the external world and going into stillness and silence. It is only then that we can observe the mind and move beyond the mind.

Figure 2: Reshaping the antaḥkaraṇa for purification

To untie the knots, one must reign in the senses and reduce the repetition of desire-driven karmas, as that is the root of the creation of saṃskāras. The ignorance of the ahaṃkāra must be removed, allowing the seeker to see things the way they are.

Understanding that one has the choice to exercise discrimination due to managing the faculties of the antaḥkaraṇa is the empowerment that the seeker needs to begin his ascent out of saṃsāra. Rather than acting mechanically as though programmed by saṃskāras and unaware of his role in building these samskāras, the vijñānavān[4] applies his discriminating intellect and holds himself accountable through knowledge of the antaḥkaraṇa. He directs the intellect to move the manas away from pursuing sensual pleasures. This reduces the ego and eventually dissolves the sense of identity through knowledge of the Self. The seeker can understand the cause of undesirable personality traits, rāgas, dweṣas, fears, and compulsions and intercept and influence them. In so doing, he becomes mindful that he is not the body, nor the (functions of the) mind, but rather, the Sākṣi or witness—the one who is aware of them. He becomes a samanaska or one endowed with a controlled mind.

यस्तु विज्ञानवान्भवति समनस्कः सदा शुचिः ।

स तु तत्पदमाप्नोति यस्माद्भूयो न जायते ॥

yas tu vijñānavān bhavati samanaskaḥ sadā śuci sa tu tat padam āpnoti yasmāt bhūyo na jāyate

That (master of the chariot), however, who is associated with a discriminating intellect, and being endowed with a controlled mind, is ever pure and attains that goal from which he is not born again.

~ Kathopanishad 1.3.8)

As avidyā is overcome by knowledge of the Self, the antaḥkaraṇa is purified by meditation and contemplation through which the subtle body progresses. This purification prepares the self for the knowledge of Brahman without distraction or deviation. The association of the intellect with the mind and the sense organs is harmonious and self-restrained. The sādhaka, who has a clean, pure, and developed antaḥkaraṇa, and whose mind is unpolluted and concentrated, does not need to go towards sense-gratification from external stimuli but turns inward to his heart for the full experience of Brahman.

[1] Bhagavad Gita 2.14 describes how fleeting perceptions of happiness and distress arise from contact between the sense organs and sense objects.

[2] Kathopanishad 1.2.2

[3] Mundaka Upanishad 2.2.9 references the knots of the heart

[4] Kathopanishad 1.3.6