Jab Zero Diya Mere Bharat Ne

JAB ZERO DIYA MERE BHARAT NE

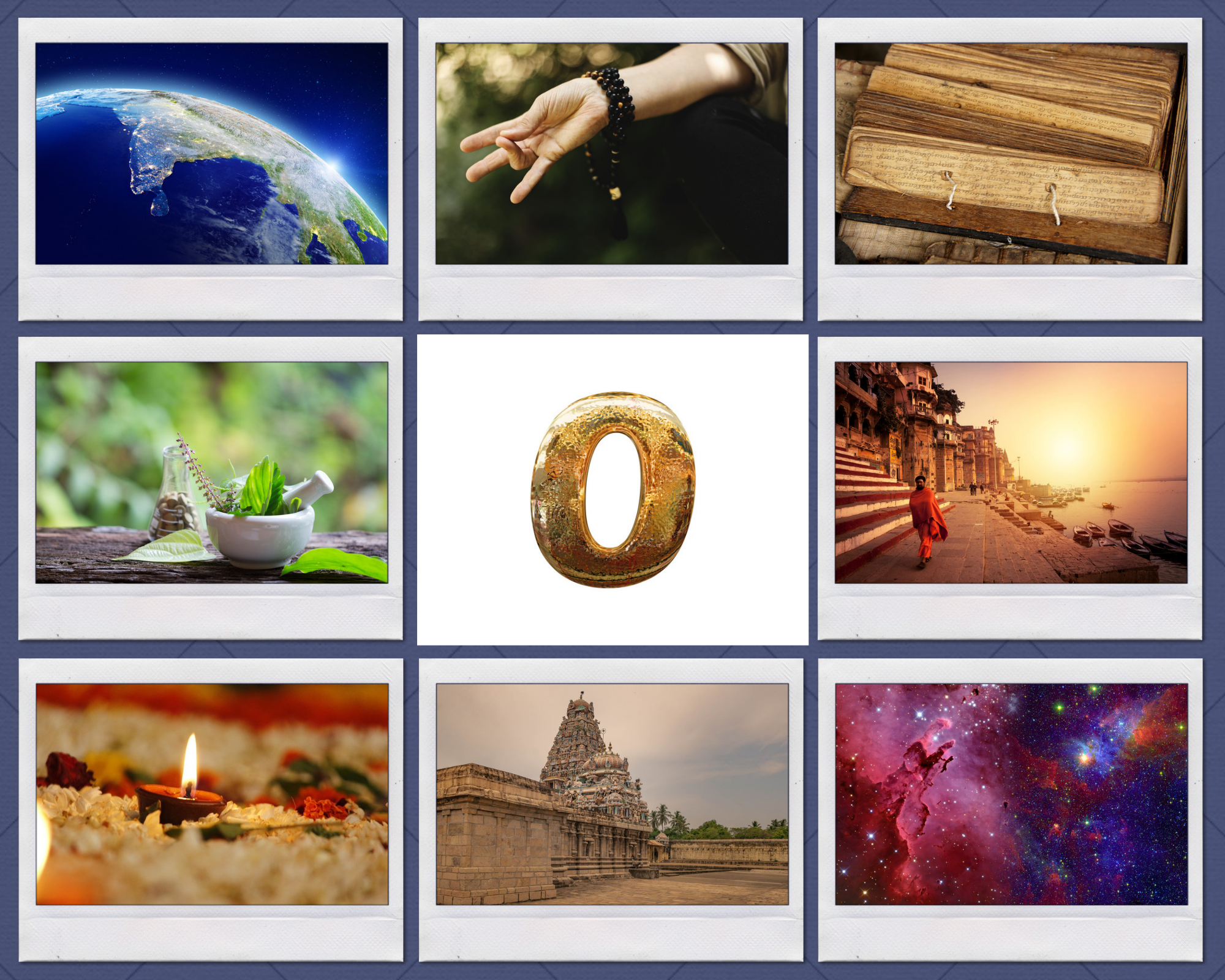

One of the most popular misconceptions about India's contribution to the world is that it begins and ends with the invention of 'zero'. Dr. Debidatta A. Mahapatra offers a timely reminder that we need to look beyond and go beyond this line of thinking, and to do this, begins with the most unlikely of sources - the silver screen!

In this blog, I call for knowledge production in Hinduism by following Hindu tenets and maxims. I will start this by recounting part of the story from the Hindi movie, Purab aur Paschim (East and West), in which the protagonist Bharat is ridiculed by Harnam for India’s post-independence poverty, its reliance on foreign countries for sustenance, and its ‘zero’ contribution to science and technology, to which Bharat says, jab zero diya mere bharat ne bharat ne mere bharat ne duniyaa ko tab ginati aayi… (it is only because my India invented zero, the world learnt counting…).

By recounting the story from the movie, I do not intend to exaggerate or undermine the contribution ancient India made to the world. Ancient India’s contribution to human civilization is unparalleled, provoking thinkers like Voltaire to pronounce ‘everything has come down to us from the banks of the Ganges’ and Mark Twain to proclaim ‘a glimpse of India is more delightful than the glimpse of the rest of the world combined’.

The Rishis in ancient India performed arduous tapasya and the great hymns emerged from the divine realization facilitated by that tapasya. The great scriptures were creation of this direct realization, pratyksha anubhuti, of the Brahman. That spiritual experience is lacking in modern India, with perhaps rare exceptions. Sri Aurobindo lamented that the modern mind is lost to ‘transient glories’ and ‘mechanical knowledge’. In his words, “small is the chance that in an age which blinds our eyes with the transient glories of the outward life and deafens our ears with the victorious trumpets of a material and mechanical knowledge many shall cast more than the eye of an intellectual and imaginative curiosity on the passwords of their ancient discipline or seek to penetrate into the heart of their radiant mysteries.”

It is also not rare that one comes across arguments that many Indian intellectuals are like copycats of their counterparts in the western world as they are happy to follow the western modes and methods of knowledge production. And this imitation is almost in every sphere, and Indian intellectuals are lacking creativity. It is not that Vedanta undermined intellectual discourse, or undervalued its significance for knowledge production, but the vision of Vedanta was certainly not the vision of a ratiocinating mind, or a utilitarian mind, that is solely concerned with relative truth, the truth that the proverbial blind men were seeking while describing the elephant.

We do not have in our midst great Acharyas like Shankara or Ramanuja, nor diplomats like Kautilya, and mathematicians like Aryabhatta. It may not be inappropriate to argue that we do not have in our midst a scholar of Vedantic vision. In the globalized world, we do not have visions of Sri Ramakrishna or Swami Vivekananda or Sri Aurobindo or Ramana Maharshi.

The dominant trend shaping the Indian intellectual mind can be characterized by this: glorification of the ancient past and disappointment about the medieval and the modern past of invasions and foreign rule. While enriched and armed by the ancient knowledge, and aware of the onslaughts, I make a call to rise again and produce knowledge inspired by the enabling Vedanta vision, the knowledge that not only compares and rationalizes, but empowers the knowers to play active roles in society to shape it in the grander Vedantic vision, in which Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam is not only a phrase of the book but also a living reality.

Neither Adi Shankara nor Ramanuja nor the other great Vedanta scholars of the ancient times knew English, nor did the modern sages like Ramana Maharshi or Ramakrishna Paramahamsa or Sri Chaitanya. My goal here is not show the English language in poor light or demean its contribution to knowledge production. English is the global language. But even in English langue, we do not come across works like Life Divine, or spiritual poetry like Savitri. Though written in English language, one could come across in these works the Vedanta vision that inspired them.

As the next year is the 150th birth anniversary of Sri Aurobindo, it provides an apt occasion to think about pace and place of Hindu thinking in the global matrix of knowledge production and meditate on methods so that authentic Hindu knowledge is produced, the knowledge that brings a larger vision to humanity, bolstering its march to the next stage of evolution, in the process of which India has been the exemplar.

Sri Aurobindo wrote, “India of the ages is not dead nor has she spoken her last creative word; she lives and has still something to do for herself and the human peoples.” So, like Bharat, the protagonist of Purab aur Pashchim, while proudly singing jab zero diya mere bharat ne, we must invoke the vision that inspired the Rishis of ancient age to address the crises human society is grappling with.

Credits: College by Suresh Lakshminarayanan includes images by Pete Linforth from Pixabay and Shutterstock.